How a few photos from 2008 still undermine attempts to tackle UK poverty

Good journalism can be undermined by damaging picture choice

by Gavin Aitchison, media unit coordinator at Church Action on Poverty

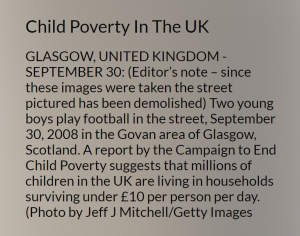

You will have seen them, though almost certainly won’t know who they are. Two young boys, kicking a football around in Glasgow.

They’re outside a building that has graffiti on it and there’s a shopping trolley in the foreground. It’s a brief snapshot in time, captured by a photographer on Tuesday, September 30th, 2008. But somehow, a few images of this fleeting moment have taken on a life of their own.

For more than a decade, these photos have been among the most-used stock images for media reports about poverty. Even when articles are nuanced, insightful and constructive, they are often accompanied by these clunking and misleading images. Now, as the impact of the coronavirus outbreak threatens to sweep many more UK families into poverty, they are back again.

On the off chance that you don’t know what pictures we’re talking about, you can see them on the website of Getty Images. Alternatively, conduct a google image search for ‘uk poverty’ and you’ll see them in results like this (the second, third and seventh shots on the top row are all from this shoot and appear countless times in media stories).

There are three principal things wrong with the way these images are used:

- They are very old and now out of date

- What is happening in the photos is hardly ever explained, and is not what you think

- They undermine and hinder attempts to tackle poverty in the UK

These pictures are undoubtedly striking and powerful, but they carry an othering effect that has grown with time. They are laden with visual tropes likely to prompt concern. There’s an abandoned trolley, unaccompanied children, a vandalised building, litter, unkempt paths. The message to viewers is: poverty exists in streets like this. And, therefore, not where you live. These scenes (even before we get to the misleading way the photos are used) display a particularly dramatised manifestastion of poverty, which skews and narrows public understanding of what poverty is.

It’s said that the camera never lies, but when you see these photos in newspaper after newspaper, they do not tell the truth.

Seeking the street

I decided to try to find where these photos were taken, to see whether they reflected reality. Then, when searching online, I found that Paul Climie, a blogger in Glasgow, had already done exactly that.

Thanks to a recognisable fence and petrol station in the background of one photo, he was able to use local knowledge to pinpoint the location. His compelling analysis show how false, dangerous and unhealthy these photos are. With Paul’s permission, I share extracts of his post below.

He writes:

“…The other thing I know about the type of tenements I recognised in these pictures, is that they too were demolished shortly after the pictures were taken in 2008.

Nobody lived in those boarded up flats. Nobody was there to care for the garden or keep an eye out for vandalism. The images fit a handy stereotype, which I believe is harmful and not particularly accurate or representative….

“These photographs of children playing amidst boarded up and vandalised houses are deceptive, … [they were] taken at a time when they were awaiting demolition and were empty… Yet every few weeks, these derelict tenements awaiting demolition are re-built in the pages and websites of the national media to illustrate ‘childhood poverty’.”

So points 1 and 2: The photos are now nearly 12 years old, and they do not show anyone’s homes, but rather a derelict building awaiting demolition on a site that was then redeveloped.

Getty, it should be said, includes this note on its site, stating that the buildings have since been demolished, but that point never appears when the photo is reused by other media. The unexplained photo remains a dominant but false characterisation of poverty. It misrepresents that neighbourhood, but the damage is much wider.

You might say it’s only an image, that lots of stock images are used by the media, and that people will read beyond headlines and photos. But no. We know pictures have an impact. People think in images and photos trigger ingrained thoughts and ideas that can help or hinder the way we see ourselves, others and our environment.

Here, the photos matter because they make poverty look remote, when we know it isn’t. Between a quarter and a fifth of people in Britain live in poverty. It is in every county, town and city in the country.

As Paul says:

“I would argue that the pictures used repeatedly to present an image of poverty reinforce this idea that the story is not about “people like me”. I don’t live in a house like that. I supervise my kids, clean my close and cut my grass. These images feed a narrative of “them and us”…

That’s the problem I have with these unsupervised children in a neglected building illustrating every single story we read on the topic, this “othering”. They are not like “us”, these poor people. We wouldn’t end up in that situation. It must be the fault of the parents, not society or government.”

Analysis of media coverage of poverty has repeatedly identified the ‘othering’ nature of reports. We aspire to be a society in which we all pull together to improve things, and where we draw on our shared humanity to tackle social injustice. Imagery that creates ‘us and them’ division undermines that. [See, for instance, work by Joseph Rowntree Foundation in 2008, the LSE in 2014, and Lankelly Chase in 2020]

The images above shows the 2008 scene, and the same spot in 2019, as captured by Paul. He writes:

“Here is the reality of that derelict street today. It may still be an area with problems, but I think we need to find a more nuanced way to talk about poverty. The stereotype we get accompanying these news stories is just that. A stereotype.”

What does poverty in the UK look like? It’s a class of primary school children, a quarter of whom will be held back by structures beyond their control and an economy that denies their family an adequate income. It’s a parent forgoing meals because even though they have several jobs, none offers enough hours in the week to cover the bills. It’s someone with long-term disabilities, who is suddenly expected to seek work they cannot manage, or see even more of their support removed by the state. It’s a child who cannot keep up with their friends during the coronavirus lockdown, because they are digitally excluded, unable to access online learning resources. It’s an underpaid worker in London, forced to compromise their safety in these worrying times, when others can choose not to. It’s a young couple who have had to move back in with parents, because the rents in their city have soared far faster than wages. It’s a hidden carer, looking after their elderly parents at the same time as caring for their own kids, so unable to pursue the opportunities that might otherwise open up.

Photos like the Glasgow ones mislead, stigmatise and stereotype, and in doing so they exacerbate ignorance. They reduce people’s ability to understand others’ lives, and therefore hinder attempts to bring people together and develop a shared understanding that can identify and bring about meaningful social change. From a journalistic perspective, these photos also hinder the very purpose of the news media, namely to inform and improve public understanding.

At Church Action on Poverty, we have spent the past five years working to challenge misleading and damaging media coverage of poverty, and we’re working with others now to press for more considered picture selection.

Others are raising similar concerns, such as here in the What’s The Problem? project.

On this particular issue, I’ve decided to act. When I see that photo now, I will email the newspaper editor, point them to Paul’s blog post, and ask them to rethink the way the portray poverty in the UK. It’s a small step, but it might just help us to end the stigmatisation of people in poverty.

If you see these photos, or other stock images that you feel exacerbate false stereotypes of poverty, let us know and you and we can together help work towards better coverage.