Make like Moses

Hannah Brock-Womack, facilitator of our Church on the Margins network in Sheffield, talks to network member Siggy Parratt-Halbert.

This blog post is mainly about not giving up.

Siggy doesn’t give up easily, it seems to me. She works where she lives in the village of Woodhouse, to the east of Sheffield, for Unlock Urban. Woodhouse is a place where everyone knows everyone. They’re justifiably proud of their long industrial history, including having one of the pits where the Bevin boys were trained. It’s just down the road from the Orgreave where the biggest confrontation of the ‘84-’85 miners’ strike happened.

Unlock aims to share the Bible with people who don’t usually read that much. It has a really laid back and non-intrusive way of working, giving people the chance to have conversations about faith, knowing that no one is going to try and convert them at the end of the conversation!

Siggy started off her work for Unlock spending several months talking to people at coffee mornings. It felt like slow work. In fact, the first two years of that job didn’t go that well. She felt like things weren’t moving in the right direction. When asked if she wanted to keep at it for another two years, she almost said no. When she agreed to keep going, she decided that it had to be be by doing something that she enjoyed, so that she could keep going, even if it was tough. And one of the things she enjoys is drawing.

Inspirational women

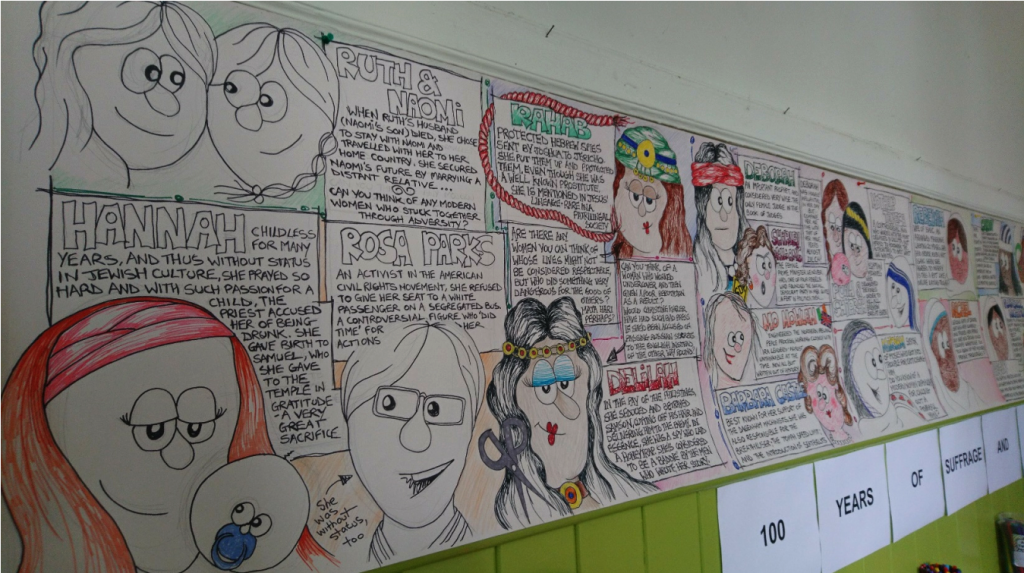

I first met Siggy when she came to our Church on the Margins reflection day here in Sheffield a few months ago. On that day, she wowed us with the cartoons she’d drawn, which are of modern-day women and a Bible character that they have something in common with. These aren’t pious women who no one can now relate to, they’re inspirational women who changed the world with their vision, like Rosa Parks and her scriptural counterpart Hannah (from the book of Samuel), or Radclyffe Hall, a lesbian and author who was ‘out’ long before it was safe to be, who’s a bit like the Witch of Endor (also from Samuel), another powerful woman who nailed her colours to the mast and was at risk of death for doing it.

This project was the thing that kept Siggy going, and got connections all around the community flourishing. She drew them at the coffee mornings and other community events, starting off with those from the book A History of Britain in 21 Women. Then everyone got involved, suggesting different women she should include. The last picture was of Jodie Whittaker, the first female Doctor Who (from Sheffield) – because where do you go from there?!

In the end she drew 51 pairs of women – including lots from the Bible that many who’d been going to church their whole lives hadn’t heard of. The people at the coffee morning are different from the people attend the church on a Sunday morning, so it was a way of getting the whole community (not just church-goers) to pull together around a shared, creative project. But it was also a way of making scripture more accessible, and bringing the tales of these inspirational women into the modern day. It makes the Bible more relevant, in a way, said Siggy, because, really, the lives we’re living haven’t changed, in a lot of ways.

Bringing the community together

Around the UK today it can feel like people are living more insular lives, needing to concentrate on their families to survive difficult times. It’s hard to make a living in Woodhouse too, so Siggy was making links with the local shops, letting them know they’re supported. There have been several community projects that involved local shop workers, including giving out postcards of the four days of Christ’s Passion that Siggy had drawn. These offered lots of opportunities for non-churchgoers to ask questions about Easter that they wouldn’t have had the opportunity to ask before. There were a lot of interesting conversations!

There’s also a homeless hostel in the village, which is quite a transient place to be. That means there are lots of young men passing through, with sometimes chaotic lives. There’s a big disconnect between those who live in the village long-term and those who are there for a short time only at the hostel. The transient community often gets blamed for anything that goes wrong. Siggy wanted to encourage folk to reach out to each other but in reality, they were a bit too scared. One thing the project has done, though, is to encourage everyone who uses the church building to want to make contact with each other. That means two church communities that use the building, as well as the karate club, breastfeeding club, and the toddlers’ group and more. She is confident that the men from the hostel will soon be included in this list. Baby steps!

As we’re both part of a Church Action on Poverty network, we talked about what being part of a church community means for people who are struggling to make ends meet. Siggy reckons that when people do go to churches that are working well, the thing they get out of it most is the family feel and the fellowship – you’re held. If anything goes wrong, or if you’ve got something to celebrate, there are people who are there for you. Knowing that other people have got your back is really valuable.

“It’s not about bums on seats, it’s about the kingdom”, Siggy said.

She hopes that churches can be seen as places where, when people have nothing, and don’t have the support mechanisms they need, they know that support is available. The faith side of things might come later.

Keep on going, even when it’s hard

The Bible Women cartoon project sounds like an incredible piece of work that really brought diverse people together. Right now it’s available to hire out, so you can bring it to your church if you’d like to! Get in contact with Unlock.

When we met we talked a lot about perseverance, and what you need to keep going when you feel like you have a passion to do something but it’s not working out. The answer in the end turned out to be quite simply: do something that you enjoy and that makes you feel alive, so that even if it doesn’t have the impact you imagine, you are still being fed, and you are less likely to get despondent. It reminds me of the quote which is a bit of a cliché, but is nonetheless true:

“Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive, and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive.”

(Howard Thurman, African-American civil rights leader)

Siggy’s other advice to those who are struggling to keep going? Be creative. Find something that gets people involved and makes your community ‘bite’ and come together. Use your gift (everyone has one!), or find that someone in your community who has the gift that you need.

And also…

“If it took Moses 40 years in the desert and he still didn’t see the fruits of the seeds that he sowed, who was I to complain?!”