Reflections on living in lockdown: grief

Church Action on Poverty trustee Stef Benstead shares reflections on how the Coronavirus outbreak is affecting her life, as someone with disabilities who is used to being on a low income. In the third post of the series, she talks about grief.

Because of my chronic illness, I’ve already done the loss and grieving process. I’ve already lost a job; lost contact with friends; been all-but housebound; seen no one but parents for days on end. I’ve experienced the loss of purpose or fulfilment, and the dislocation of no longer having an idea of where the future is going.

It is best to let yourself feel the grief, rather than hide or deny it. And don’t feel that your loss isn’t worthy of grief: it is.

Having gone through that, I can assure you that it is possible to come out the other side to a sunny life. But there is no escape from going through the grief, and that is sad and painful. It is best to let yourself feel the grief, rather than hide or deny it. And don’t feel that your loss isn’t worthy of grief: it is. Sometimes it’s the smallest things in life that mean the most.

It’s difficult refusing to do things that you want to do, particularly when other people want you to be there, but the lockdown removes that mental pressure. The mental strain I face regularly – shall I go to church today; shall I go to homegroup; can I go to that conference; can I finish this project – is all gone, because the answer is “no”, and I didn’t impose it. Someone else is now safeguarding my physical health for me! In that way, the coronavirus is giving me a much-needed holiday, with much less mental strain than when I have to choose for myself to miss out on something I really want to do.

The Bible tells us,

“Now listen, you who say, ‘Today or tomorrow we will go to this or that city, spend a year there, carry on business and make money.’ Why, you do not even know what will happen tomorrow. What is your life? You are a mist that appears for a little while and then vanishes. Instead, you ought to say, ‘If it is the Lord’s will, we will live and do this or that.’”

(James 4:13-15)

It has been easy in the West to neglect the truth of that verse and how to live by it. But the truth is that there is only one constant in life, and that is God. There is only one constant task, and that is to live to glorify God. That path will never leave us. Like a little child holding her father’s hand, we do not ask to know the whole route, but only to walk what is before us. We know how to walk; we have our best friend, protector and guide with us; and with that we can rest content.

Stef Benstead’s book Second Class Citizens: The treatment of disabled people in austerity Britain is available from the Centre for Welfare Reform.

Stef Benstead’s book Second Class Citizens: The treatment of disabled people in austerity Britain is available from the Centre for Welfare Reform.

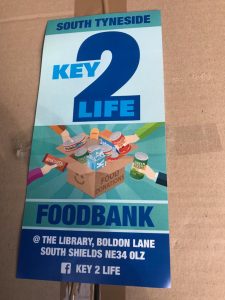

Our foodbank manager, Jo, has health issues so is working from home and most of our trustees are self-isolating. However, we were delighted to be ‘loaned’ Pauline, who would normally be running the Methodist shop in the town centre, which has temporarily closed. Pauline is working three days a week at the Foodbank to make sure protocols are followed and managing the finances. A great example of cooperation and sharing of resources! It is a big relief because otherwise we had no senior person able to actually go to the foodbank to support the volunteers.

Our foodbank manager, Jo, has health issues so is working from home and most of our trustees are self-isolating. However, we were delighted to be ‘loaned’ Pauline, who would normally be running the Methodist shop in the town centre, which has temporarily closed. Pauline is working three days a week at the Foodbank to make sure protocols are followed and managing the finances. A great example of cooperation and sharing of resources! It is a big relief because otherwise we had no senior person able to actually go to the foodbank to support the volunteers.