Our media work is driven by the knowledge that people in poverty understand it better than anyone else.

That maxim may sound obvious, but while poverty attracts much attention in the UK media, the coverage is often flimsy and fleeting because people who truly understand it are left out.

We launched our poverty media unit in 2015 because of growing concern about the way the issues were being reported, and the fact that people in poverty were being routinely misrepresented or ignored altogether.

A big part of our work in the past five years has been in partnership with the National Union of Journalists, and that work has taken another promising step forward.

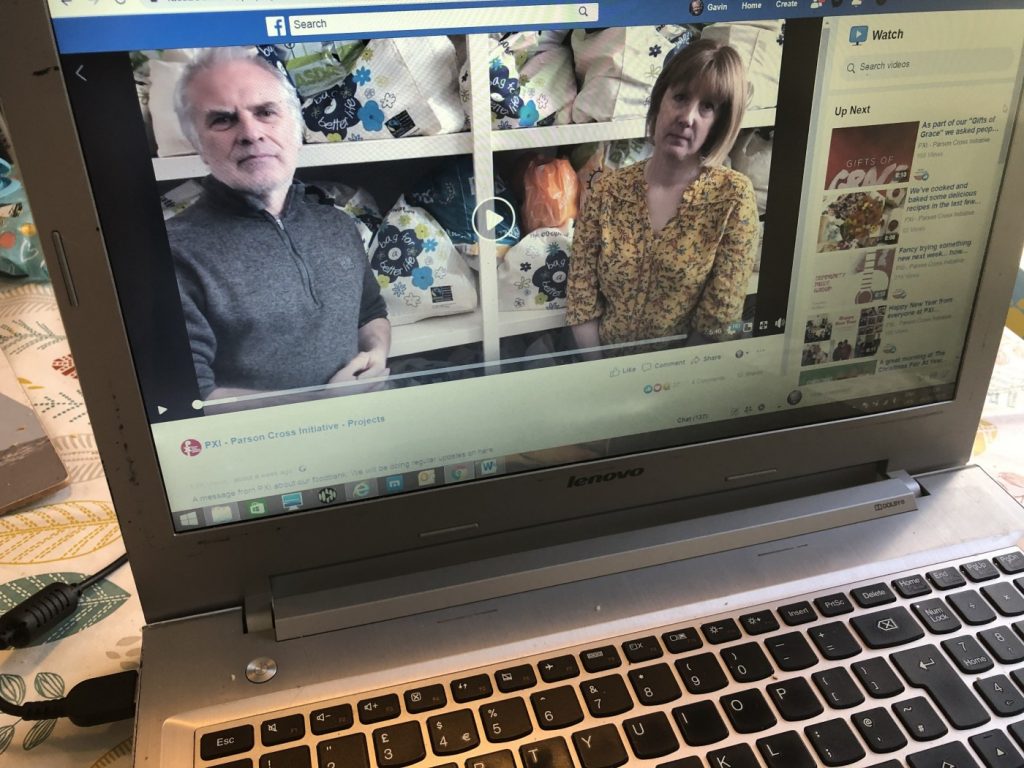

Supporters may recall that in 2016, we worked with the NUJ and people in poverty to produce a reporting guide, and in 2017 we worked with the union and the Reporters’ Academy to produce this short film:

2020: Further progress

In March, the NUJ hosted a round-table discussion event at its headquarters in London, for journalists, people in poverty and charities including Church Action on Poverty and Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Martin Green, one of our trustees, was among six people with experience of poverty in Halifax, York and London. They were joined by around 15 journalists, consisting of reporters, photographers and members of the union’s ethics committee. Further work will also now follow, and we hope to update the guide. (The event was held in the first few days of March, prior to the advice against group gatherings)

Topics of conversation at the event included the way that over-dramatic stock images skew public perceptions, painting a narrow and extreme understanding of poverty in the public eye.

We talked also about the lack of diversity in newsrooms, with few journalists having grown up in poverty.

Sydnie Corley, from York Food Justice Alliance, challenged media preconceptions about what audiences want. “Journalists say they print what people want to read – but why not challenge them more to read something that challenges what they think?”

Mary Passeri, also from York, recounted her positive and negative experiences with journalists, and said: “You shouldn’t be making people in poverty feel like they’re on trial, to prove what they’re saying. Of course, fact-check things, but interview more sensitively and sincerely than sometimes happens.”

Fundamentally, the speakers with experience of poverty called for deeper relationships with journalists and a more collaborative approach.

As Diana, from ATD Fourth World, said at the event: “If you are interviewing someone who might never have been asked their opinion before in their life, then it’s really important to ensure they have the opportunity to influence your narrative. We want to be part of designing stories together.”

Too often, journalists seek personal input only when a story is already written or nearing completion. ‘Case studies’ are sought for preconceived narratives, with little regard for the broader insights an interviewee may bring.

We know severe editorial cuts mean deeper coverage is not always easy, but several organisations (including Church Action on Poverty, Joseph Rowntree Foundation and On Road Media) are all now working with journalists and people in poverty on an ongoing basis, to support and enable coverage that is responsible, well-planned, considered and collaborative. There is great potential for further enlightened and effective work.

A positive example

A few weeks earlier, that very approach showed how complicated issues can be conveyed powerfully and clearly to a large audience. Mary and Sydnie from York both campaign around food poverty but also have personal experience of the complexities and inadequacies of carer support in the UK. We worked with Joseph Rowntree Foundation and BBC News over a series of discussions, and Mary and Sydnie then told their stories on the BBC News at Six, to an audience of millions, showing how the lack of support keeps people trapped in poverty, and outlining what could help to make a difference.

You can read and watch that story here, on the BBC website.

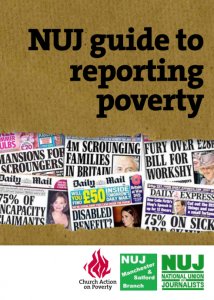

NUJ guide to reporting poverty

The original version of the NUJ guide to reporting poverty was produced in 2016 by Church Action on Poverty and the union’s Manchester and Salford branch.

The original version of the NUJ guide to reporting poverty was produced in 2016 by Church Action on Poverty and the union’s Manchester and Salford branch.

It was led by people with personal experience of poverty, sharing their views on what would constitute good journalism that might make a difference to society. It contains contributors’ own ideas and experiences, and also includes useful information that could enhance journalist’ understanding of the underlying causes of UK poverty.

Budget 2023: Speaking Truth To Power reaction

Budget 2023: a precious chance to bridge the rich-poor divide

Books about poverty: some recommendations for World Book Day

Dark Holy Ground – autobiography of a Church Action on Poverty campaigner

Undercurrent book review: “you can’t kick hunger into touch with a beautiful view”

What does it mean to be a church on the margins?

News release: Poor communities hit hardest by church closures, study finds

We need to dig deeper in our response to poverty

Gemma: What I want to change, speaking truth to power

Meet our five new trustees

Feeding Britain & YLP: Raising dignity, hope & choice with households

Parkas, walking boots, and action for change: Sheffield’s urban poverty pilgrimage

Dreamers Who Do: North East event for Church Action on Poverty Sunday 2024

Autumn Statement: Stef & Church Action on Poverty’s response

Act On Poverty – a Lent programme about tackling UK and global poverty

You can help out today...

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea.