“All it needs is people willing to listen”

Stef Benstead looks back on her experiences as part of the first Manchester Poverty Truth Commission.

I was invited to join the Manchester Poverty Truth Commission by Niall Cooper, after he had met me a few times at various Christian conferences on poverty and related issues. It sounded like a great idea that addressed one of the challenges I regularly come up against in my work on disability and the social security system – that those with power don’t listen to those affected by their policies, and end up making bad policies due to wrong beliefs or assumptions about what the issues are and what are the causes, and therefore the solutions, of those issues.

It’s really important that people with lived experience of an issue are an equal part of the policy-making process. Many of the problems with Universal Credit are because the government didn’t listen to people in poverty and on benefits; problems with benefits for sick and disabled people would also have been avoided if sick and disabled people had been listened to.

But it’s also hard for people with lived experience to get involved. It’s not just a lack of time, lack of contacts or lack of knowledge about how to get our voices heard. It’s also that the bureaucratic barriers that have built up and the harm that flawed policies have caused have built a painful wall between policy-makers, such as the local council, and the people affected. When policy-makers do want to start listening and put into practice what they are told, it isn’t enough to simply say that they’re listening. First there needs to be a relationship between the two sides, so that those of us in poverty and with lived experience of the impacts of policy can be reassured that this time the listening is genuine and the outcomes will be real and positive.

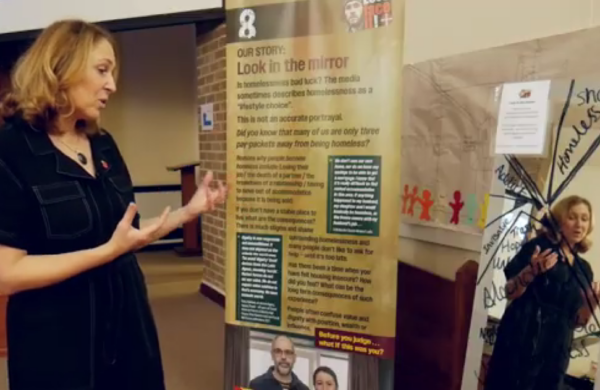

This is what Poverty Truth Commissions achieve. The time taken to share personal stories revealed a common humanity which I at least wasn’t expecting. I thought there would be a middle class/poorer people divide. In fact what I heard was business and civic leaders who had grown up in poverty, brought up by single parents on council estates; and grass-roots commissioners who, like me, had grown up middle-class only to fall into poverty later. Commissioners on both sides had experienced recent bereavement or relationship breakdown. These stories of our lives levelled the playing field: we realised that where we had ended up wasn’t representative of who we are as people, and that was as true for the business and civic commissioners as for the grass-roots commissioners.

The biggest impact for me was when one of the business and civic leaders took an idea that I had put forward, which from her perspective was unaffordable and unworkable at that point, and came back a month later with a revamped idea that could be made to work. I’m still working on this idea now and hope it will eventually come to fruition.

The PTCs break down barriers between the people who usually make policy and those who usually merely receive it. It does this by creating relationship between the two sides, teaming us up in a common fight against poverty and inhumanity. It can be a transformational process with ripple effects that continue long after the commission itself has formally finished. All it needs is people willing to listen.

Stef Benstead is a trustee of Church Action on Poverty, a grassroots commissioner in Manchester Poverty Truth Commission, and the author of Second Class Citizens: The treatment of disabled people in austerity Britain.