‘Poverty may be complex, but it is not inevitable’ (part 2)

Nick Waterfield, chair of the local Church Action on Poverty group in Sheffield, offers further thoughts on the ‘complex’ reasons why people use food banks.

Nick Waterfield, chair of the local Church Action on Poverty group in Sheffield, offers further thoughts on the ‘complex’ reasons why people use food banks.

I want to add to the discussion with some further thoughts around the existence and role that food banks are now playing in UK, today I’m taking part in a roundtable event at University of Sheffield, (with friends from UTU – Urban Theology Union, and Sheffield Church Action on Poverty) about Theology & Food Poverty and some of the points raised here will also form part of that discussion.

At some level we can be complicit in wanting or needing poverty and food insecurity to continue, in order to serve our own desires to ‘help the poor’

To start, there is sometimes an assumption by many that food banks and churches simply act out of charity and in response to biblical passages such as Matthew 35:25, and that this at some level makes us complicit in wanting, or needing poverty and food insecurity to continue in order to serve our own desires to ‘help the poor’. Now clearly charity, and the desire to help alleviate the dire situations many people find themselves in, is part of the motivation, and for some I guess it may not go any deeper, however from my own experience in North Sheffield this has not been our sole approach or intention. We’ve tried to operate much more along a basis of standing in solidarity with our neighbours in need; of listening to and learning from the life experiences we encounter, and importantly being open to being challenged and changed ourselves by the things we share.

Food is not a commodity to be bought or earned, but a gift from God to be shared

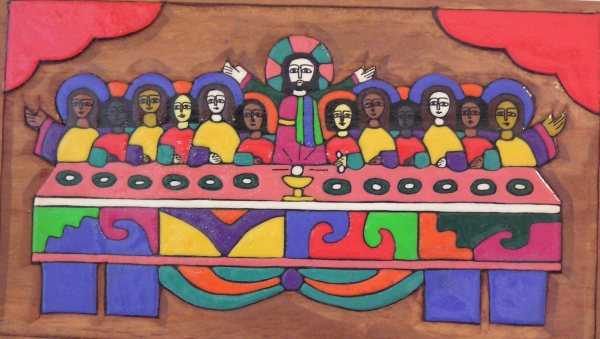

As Christians, we should attempt to hold a picture of the food shared through food banks as moving us nearer to an act framed by the Eucharist feast rather than simply an offering of charity and alms to the poor – food not as a commodity to be bought or earned, but as a gift from God to be shared. Of course that’s not easy, those of us who operate food banks cannot simply ignore the power (and authority) that roles gives us over others, but we can choose how we hold that power. We can either assume the mantle of serving in some less formalised extension of the welfare system (filled with rules and entitlements), or we can seek to place ourselves, to some degree at least, “at odds” with the system. Some food banks limit the number of referrals any family can have at any time, (often three times in a given period) – we’ve never imposed such a limit, we’ve always said “For as long as the need is there….” we are willing to offer support, our statistics show that despite this most people rarely come more than 3-4 weeks without a break. For the record, we’ve never (since opening the doors in 2010) turned anyone away without food regardless of referral vouchers or the like. Crises, and for most people food banks are still a place to go only when facing a crisis, don’t always stop after three visits (or three weeks) sometimes they can drag on for months. When someone came to us recently and said “I’ve been told by housing they won’t give me another referral because I’ve had my three ….” our response was, “Well here’s some food for this week, go back and tell housing there’s no set limit to how many times they refer you”, and of course we’ve gone back to referrers too and told them the same. We aren’t asking referrers to limit access, simply to assess need, and hopefully to use food bank as a support until they can find a solution.

At their best food banks are turning commodities into gifts and transforming bureaucratic referrals into genuine mutual relationships

So why bother with referrals at all you might ask, and it’s a good question. Partly it’s about rationing and managing the food we are given (and also therefore a fear on our part we could not cope adequately with an unrestricted demand), in part it’s about an accountability to those who donate (yes we can say that people coming are genuine and have a defined need), it’s also about making sure support is being given for some of those more “complex” underpinning issues. Knowingly or unknowingly, willingly or unwillingly, food banks operate effectively as a sub-currency, where inadequate incomes are subsidised through food. At their best food banks are turning commodities into gifts and transforming bureaucratic referrals into genuine mutual relationships, where personal complexities can be more fully understood and supported.

We’d hoped that food banks were a temporary phenomenon, it appears they may not be!

There is one big problem with food banks – the problem of normalisation. Increasingly food bank collection points can be found in more and more supermarkets, where shoppers simply add to the stores sales by buying extra to drop in the box. What does this cost the shop? Nothing – in fact it merely adds to the sales figures, and helps tick the corporate responsibility box. Don’t get me wrong – those of us running food banks are grateful for every item bought and donated, but the problem is that its all becoming “normal”. We’d hoped that food banks were a temporary phenomenon, it appears they may not be!

The hardship people are facing is real, and it’s long-term; I leave the last words to one man who came to our food bank last Friday, who said: “People are desperate so they need help. ….. I have had no gas since November because of debt. If you have no money you can’t afford to pay for utility bills” #FoodBankVoices

Reblogged this on rainbow5934.