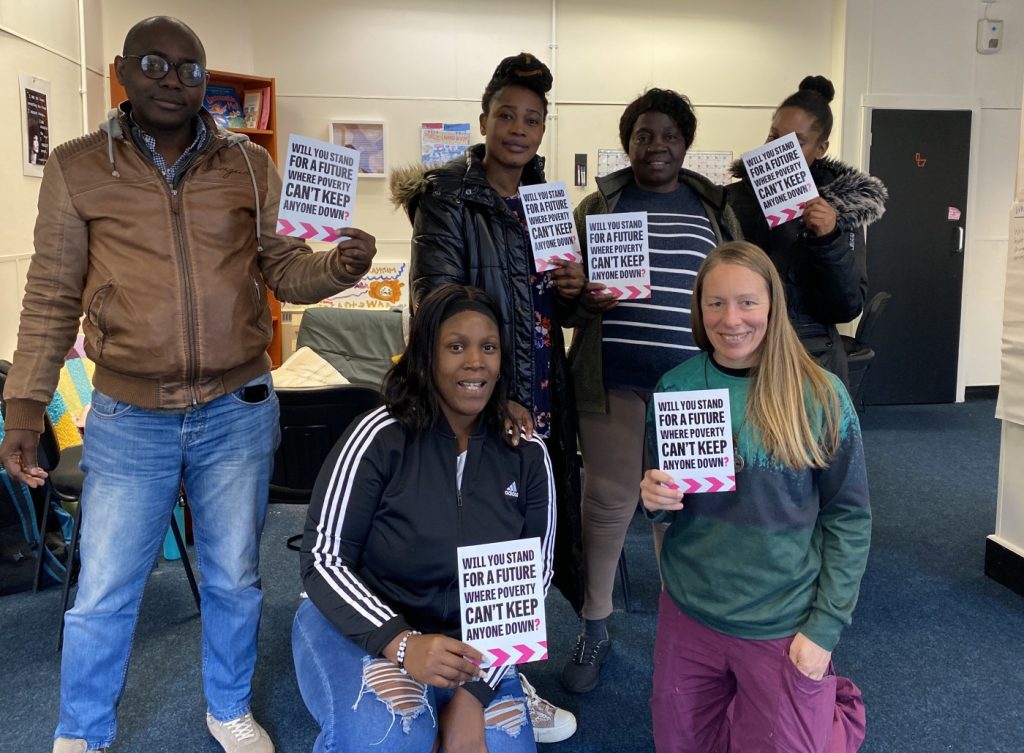

Stoke on Trent hosts the third of our Let's End Poverty Neighbourhood Voices conversations.

We’re in Stoke-on-Trent, where eight local residents are discussing the city, its challenges, and their hopes.

As it happens, the conversation took place the day before the General Election date was announced, but even then it was still on people’s minds.

We’re here for the latest in the Neighbourhood Voices series: a chance for people in communities across the country to have their say on their community, its strengths and challenges, possible solutions, their hopes, and the issues they would like election candidates to prioritise.

Stoke snapshots

People here give rapid snapshots of Stoke:

- Life expectancy is well below the national average.

- It has England’s highest infant mortality rate.

- It’s got some of the lowest disposable income in the country.

- But on the flip side, it has remarkable community spirit

- And it was named the kindest city in the country during the pandemic.

“We might be poor, but we are blinking well kind,” says Danny, chief executive of YMCA North Staffordshire. “In Covid, the papers said Stoke was one of the kindest places, with most community action. There’s still that real neighbourhood kindness here in Stoke.”

Issues raised include job opportunities (particularly for young people), wages, transport links, the city’s reputation and narrative, urban investment, and hope.

Economic issues

Danny says much of the city’s historic identity came from the potteries, which once supported tens of thousands of jobs.

Danny: “It’s a very working class city; there are very few middle class people. People want something to be proud of. When I was a kid, Stoke was as good as anywhere else as a city. Now, everywhere seems to have been improved, apart from us.

“I think towns and small cities in Britain have been completely ripped off. You can see huge development in the big cities, like Manchester, but Stoke has had very little. We are the proof that trickle-down economics is a load of rubbish.”

John: “Money goes out of Stoke, and so does talent. When kids do well, they leave. Most of the highly-educated and socially-mobile young people want to live in Manchester, London, Glasgow, Nottingham – they don’t stay here. And even a lot of the top earners and leaders who work in Stoke, live outside it.

“There’s really good friendship and loyalty in Stoke. But parochialism is a huge negative. There’s a culture of suppression of ambition. When kids grow up here they go away and then they are surrounded by people who expect to be successful and expect to have a good lifestyle, but a lot of people in Stoke don’t expect that. There is this poverty of aspiration we have to try to get to somehow.”

Nicky: “Stoke has a high rate of setting up businesses, but it lacks some of the professional sector to help that thrive, like accountants and legal professionals.

Dan B, a youth ambassador at YMCA: “When we leave school, people are expected to do warehouse jobs rather than getting interested in progression. There are a lot of closed down business and shops. You get dropped into low-paid jobs.

“When I left school, I knew I wanted to be in the type of role I am now (a youth ambassador), but in 2016 there were not many opportunities like this in Stoke. Maybe in Birmingham, but not here. I got a painting and decorating job but I hated it, it wasn’t what I wanted to do. Then there was an apprenticeship here – but there still wasn’t a lot of this type of role in Stoke.”

Danny: “There is a real lack of example that things could be better. There can be a ‘this’ll do’ mentality. People know what having nothing is like, but there’s still a fear of ending up with less than nothing – that’s the poverty that rich people do not understand, when they just talk about aspiration.”

John: “Stoke people have generally got a good solid character, and that’s why a lot of people do well. I think there’s a lot of low-level entrepreneurialism, but maybe not enough confidence. But people who break through do well, partly due to that affable personality.”

What do you cherish about Stoke?

Nicky: “People are very proud of our heritage and the arts. Our assets are another positive, like our green spaces – we are a very green city. Most neighbourhoods have access to green space.

“Also, if you put community events on, they are embraced massively. Stoke has one of the highest rates for community involvement and events. If there’s a big local event, everyone is out for it. People want to do stuff, and engage and get out.”

Nnaeto, chaplain at the YMCA: “This is my fifth year in Stoke. For people who have come in from elsewhere, our lens is different. We do not know all the history, but we see the opportunities. It’s central, you can go anywhere, life is fairly cheap, houses are less expensive here.”

What are the stories of Stoke?

Nnaeto: “We talk about the danger of a single story. If people look at just one angle, they miss a lot of different sides of things.”

Nicky: “If we are constantly telling young people they live in a poor city, what is going to happen? We have gone for World Craft City status, and the judges felt it was such a special place. But interestingly, the five people who talked about how wonderful Stoke is were all people who had moved here.”

What gives you hope? What would you like to be the story of Stoke?

Nicky: “That we are a city of crafts. We are a place for creatives and entrepreneurs to be birthed, and we will nurture and look after people.

“What are the positives of the city, and how do we create hope for the future? For me, it’s the community and the craft and the location.”

Linda: “If we teach some of the history, it would help have aspirations again. We have the potential to be a tourist destination that people visit. We have the historical things that would attract people, and a canal system.

“We are stuck in the past sometimes – but stuck in the negative past, not the positive past. It’s like Stoke has a really bad advertising team!

”There are glimmers of hope, like in Hanley, there is a new Kurdish restaurant opening there, and across the road, the old DWP office is now a shop, and next door is a Caribbean shop. There are a lot of different cultures opening on the street. People have moved here and are making the most of it.

“If you took somewhere like Burslem High Street, and 20 creatives, and covered the rent and utilities at first, that would be thriving.”

Bishop Matthew Parker: “We all need to know our story, but we need not be defined by that past. Stoke has produced a lot. It wasn’t just creating for the industrial revolution; it was creating things of beauty.”

Dan: “A lot of young people here have talent but it never gets seen or heard. There’s a lot of hidden talent and people never get the opportunity to be heard, or seen or given a chance. When I started here, I was very shy, I wouldn’t talk to anyone, or I’d go bright red.

“When my manager told me about the youth ambassador role, I thought they were having me on! But I knew it was an opportunity to develop my skills. Young people need more of that kind of opportunity to build themselves up, to know they can go for higher roles, maybe one day the CEO role. Companies in Stoke should be giving younger staff more opportunities to go for the higher roles.”

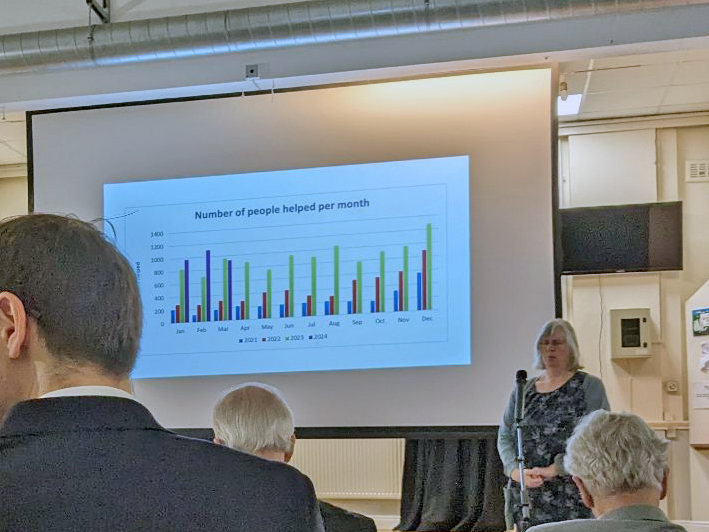

What is making a difference, or could make a difference?

Nicky: “The city was a real target before for the BNP and some politicians and press have tried to turn the community against each other, and sow division. But embracing diversity can be a real strength for the city.

“A lot of our young people here at the YMCA were talking about poverty setting them back, and how they felt trapped – whereas some of the people who have moved here from somewhere else felt they had the power to change their futures.

“What we are trying to do as the YMCA is unlock the kindness of Stoke people who left the city and done well for themselves. We send young people to Stoke expats, such as to a farm in Canada, to learn and see opportunities.”

“Another thing that helped was EMA (Education Maintenance Allowance). That was really good for the city. Young people were getting £30 a week so could go to college, and got a free bus pass. We saw a huge increase in young people able to invest in their future.”

Becky: “Yes – EMA really helped me. I had been homeless before I came here, but then I did childcare at college and now I’m involved in activities work.”

What would you like election candidates or the next Government to prioritise here?

Becky: “Transport links for me. I used to live in Burton on Trent, and it would cost me £9,80 on the train to go visit my parents. It’s only £2 on the bus, but the buses aren’t great. I go every few weeks to see my family, but it’s hard. There should be better bus passes for young people. So transport is the big thing for me, and general opportunities.”

John: “Connectivity in the area is shocking, partly due to geography. Most cities have a donut model, with a city centre in the middle. Stoke became a city, but it’s history is as 6 or 7 industrial towns, so it’s more of a sausage shape. It’s the only polycentric city in the UK. Since austerity, bus services have got worse. There are virtually no buses after 7pm on a Sunday.”

Dan B: “We’re talking about situations that are serious. When I talk to MPs, I feel that they’re listening but not understanding the real value of young people’s opinions and what their struggles are. And there are people in older generations who would love to work but can’t. We need to hear from more young people in these situations, who understand what it’s like for young people. They need to take us seriously.”

John: “I have seen so many regeneration schemes, Government plans all relying on private sector investment. We need regional focus and regional banks that operate for the region. There’s bad politics between Stoke and Newcastle-Under-Lyme, connecting to difficulties with councils. If you had a North Staffordshire regional focus, you would then have the economic area to do more.”

Nnaeto: “I want them to tell a more hopeful story of Stoke. Hope is the one thing, the most important thing people need. It’s easier for me, because I see it with a different lens. When I sit with young people, it’s difficult for them to see that there is hope but they do not need to be pulled down by negative narratives. Spread more hope.”