100 people from across the UK gathered in Leeds for the 2023 Dignity For All event.

It was a unique new gathering, bringing together a vast range of people, groups and organisations who want to see an end to poverty in the UK, and who want to find ways to rebuild the dignity of people and communities.

Dignity For All: what took place

The event included workshops, presentations, stalls, discussion groups, panels and lots of new introductions and conversations.

It’s impossible to capture everything, but these photos will give you an idea of what happened, and this blog aims also to give you a flavour of what was said – and some ideas for what to do next.

Dignity For All: in pictures

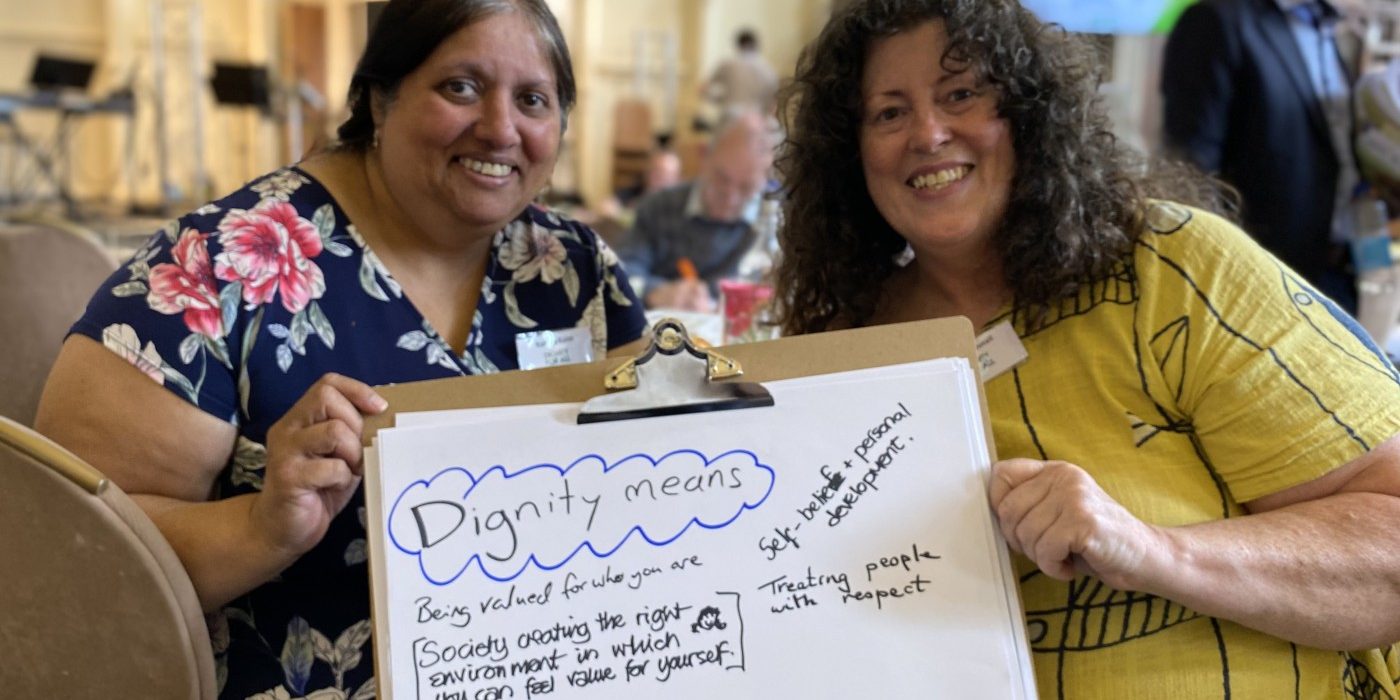

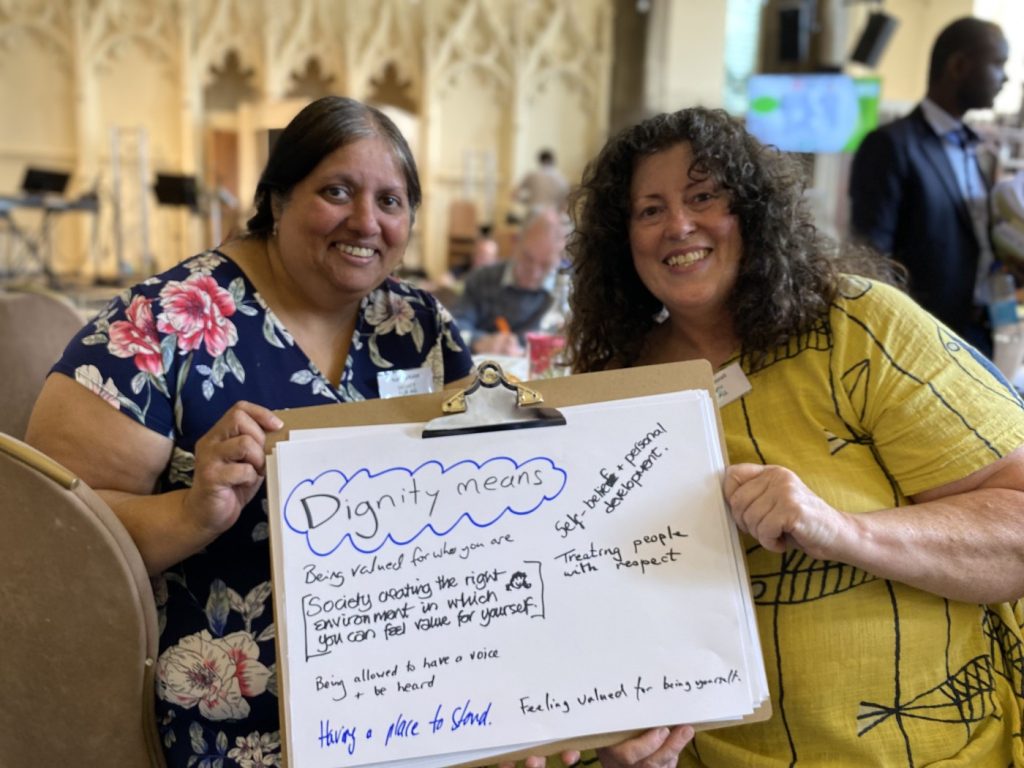

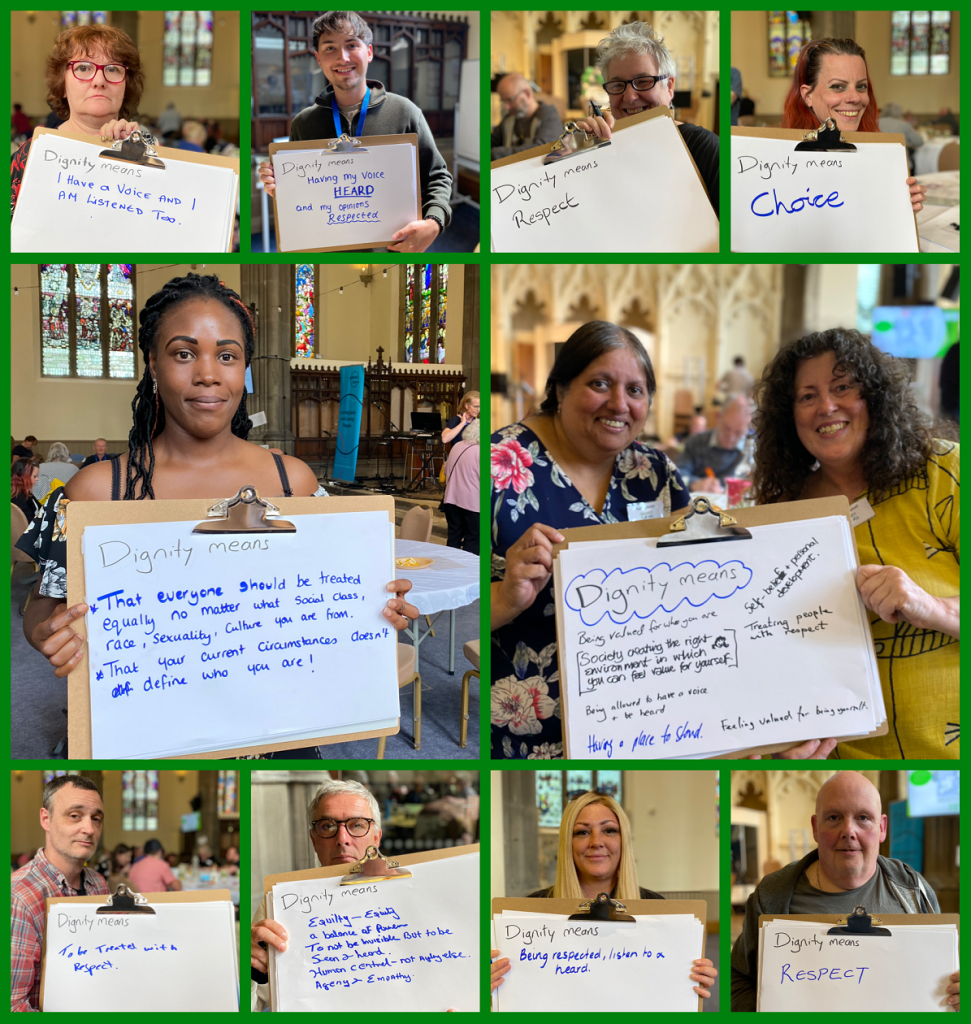

During the day, people were asked to write what dignity means to them. Some answers are shown below:

Dignity For All: what people said

Dignity For All: who was there?

The conference was organised jointly by the APLE Collective, Church Action on Poverty, and the Joint Public Issues Team.

People from a wide range of groups, churches and organisations, including Christians Against Poverty, the Poverty Truth Network, Self-Reliant Groups, the Trussell Trust and many more.

Dignity For All: what next?

One of the most pleasing outcomes on the day was the overwhelming consensus that this should not be a one-off event.

Speaker after speaker spoke of the need to build on this moment, to harness our collective expertise, insight and desire, to press for a faster end to poverty in the UK.

Various ideas are being discussed already, and attention is already turning to Challenge Poverty Week in October, another great chance to raise our voices together.

You can find out more about how to get involved at the links below.