More than 20 members of various churches across Sheffield came together to take part in the annual Sheffield Church Action on Poverty Pilgrimage, which raises awareness and understanding of how poverty is affecting people in different parts of Sheffield.

This year, our local group in Sheffield staged a three-mile circular walk, focusing on Darnall.

People attending the Pilgrimage heard about the challenges to mental, physical and financial wellbeing in Darnall posed by the Covid pandemic and lockdown, the various initiatives trying to overcome those problems, and the challenges they had faced.

They also heard from local councillor Zahira Naz about the particular problems facing families from ethnic minorities in Darnall, who had faced unfair accusations of failing to isolate and self-distance during the pandemic.

Councillor Naz said the reality was that many ethnic minority families had several generations living in the same household.

Vulnerable grandparents shared houses with family members working in occupations, including the health services, where they could be exposed to Covid as well as grandchildren who were still going to school.

To make matters worse, many families traditionally had one breadwinner, and for those working in shops, takeaways, restaurants, taxi firms and a number of other occupations, there was often no financial support.

Councillor Naz spoke of efforts she was involved with to source food, and in particular Asian food, for people in financial difficulty, which expanded into providing activity packs to keep children amused and toiletries when they were in short supply.

She said the one good thing to come out of the experience was the community cohesion it created:

“The community came together – churches, mosques, local organisations – and between us we formed relationships. None of us could have done this by ourselves, but between us with that passion to support people in our communities to make sure nobody went hungry brought us all together.”

Pilgrims heard about the work of the Church of Christ, including its role as a ‘Partner Hub’ for Food Works, the Sheffield-based social enterprise that collects surplus food that would otherwise go to landfill.

The not-for-profit organisation distributes the food it collects in boxes and as cooked meals for the vulnerable, the lonely and care workers who haven’t time to cook and started producing frozen food during the lockdowns.

They also heard about the work of the Living Waters Food Bank and the Church of England and Church Army Attercliffe and Darnall Centre of Mission.

Revd Gina Kalsi and her husband Kinder, a captain in the Church Army, arrived to lead the Mission at the start of the first Covid lockdown.

Tackling food poverty and isolation became one of their major activities as they found a number of socially distanced ways to connect with the community.

When a local bakery offered them its unsold fresh bread and cakes, they began delivering it to local people in need.

Gina Kalsi says once social distancing eased the time needed for deliveries went from one hour to a full afternoon as people, desperate for human contact, invited them in for a chat. What started as a chat rapidly turned into ad-hoc support sessions as people started asking them for help, including with completing forms.

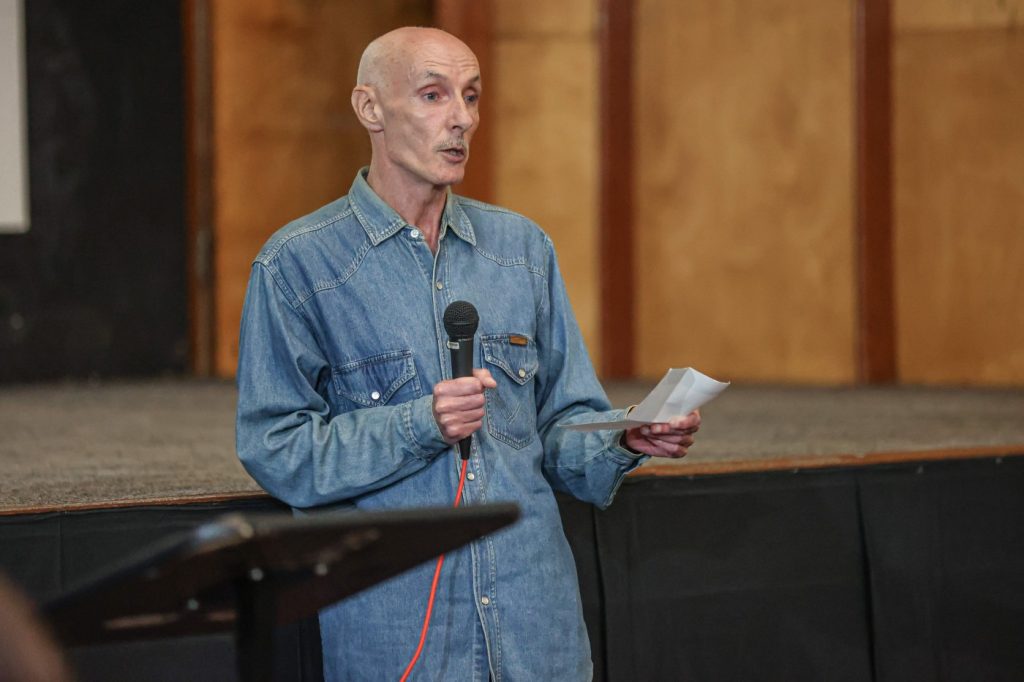

Niall Cooper, director of Church Action on Poverty, asks: How do we build dignity, agency and power together as a society?

Niall Cooper, director of Church Action on Poverty, asks: How do we build dignity, agency and power together as a society?