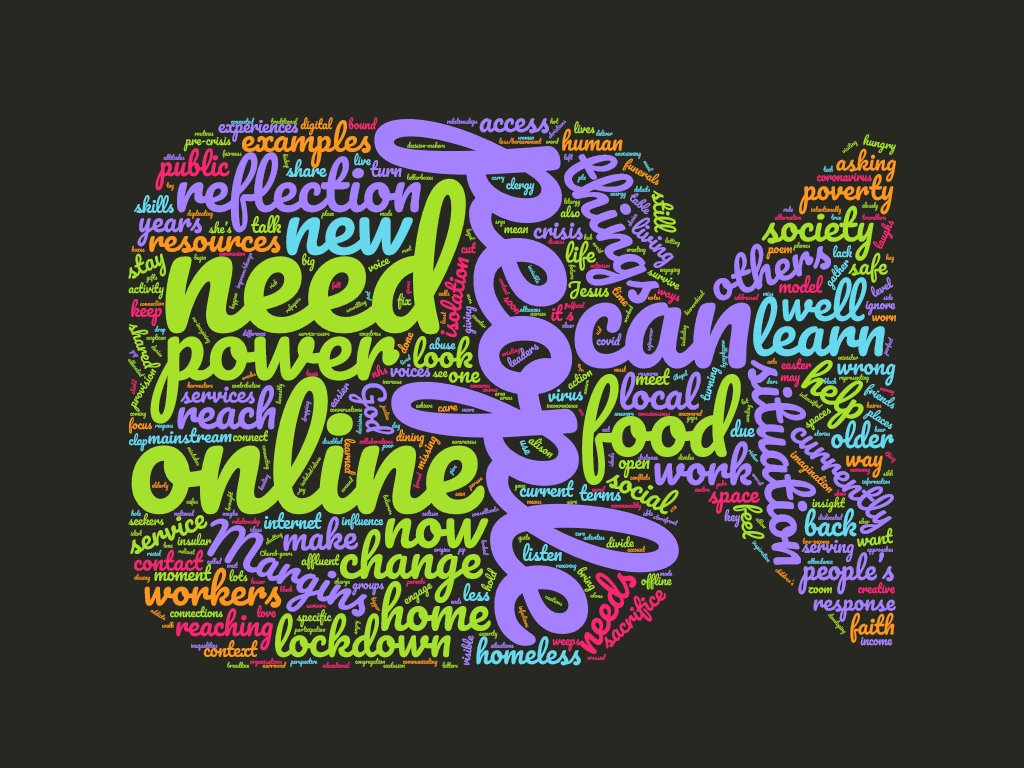

A report from our 28 May online discussions on what it means to be church on the margins during the pandemic.

Opening reflection from Revd Raj Bharath Patta, on ‘Reimagining Church Today’

How is church being missed today by the community around us?

- Online church is reaching thousands more people than before.

- Are we creating new communities – including people who were not church members before (people who were excluded or marginalised).

- Some people really miss the regular church service.

- God is present in unexpected places.

- Worship, fellowship, communion.

- What is the church for (beyond the church community/friendship)? If the church has no impact in the local community what is it for?

- During C19 we have found God in the community, mutual aid, helping people.

What is our dream if the church has to be reborn? (How do we achieve this?)

- What does ‘church membership’ mean? It does not have to be weekly attendance.

- Church language can be off-putting for new people (e.g. ‘unchurched’).

- Small dreams are important (as well as big dreams).

- Be real, authentic. Walk alongside people. Show God’s love.

- We need a liturgical revolution.

- We need to dream big – a revolution for society.

- Doughnut economics – an alternative to growth economics (see Ted Talk and book by Kate Raworth). People are stuck in the hole in middle, we need to reach out to them.

- Doughnut theology – we need the church to think in terms of people and need, not growth.

- Participation in and with the community (e.g. SRGs, Messy Church). Do not separate the church and community into ‘projects’, see it as a whole.

- Rethink the way we do ministry.

- This could be a moment of transformation for the church and wider society.

- Zoom church is more accessible for some people (e.g. families, people with disabilities).

- We need safe spaces in the community for people of different faiths to come together.

- Reflect on our activities annually and drop one to create energy for something new.

Research and Information Officer

The church must be at the heart of the mishmash of local life

What are the challenges and opportunities in your neighbourhood? And where does your church fit in? Those are two of the questions that people at …

Volunteers needed!

Could you help us reach out to supporters and churches for the next Church Action on Poverty Sunday?

Urgent: Ask your church to display this poster on Sunday

Churchgoers are urged to speak up against the Government’s harmful and immoral cuts to vital lifelines. Please, join the calls. The Government is proposing to …

The town of 250,000 that revolutionised its food system

The town of Reading, in Berkshire, has revolutionised its community food work in the past two years. Faith Christian Group has opened eight Your Local Pantries …

Say no to these immoral cuts, built on weasel words and spin

Labour said they would put disabled people at the heart of everything they do. But instead they have shoved us to the very edges. The …

Dreams and Realities in our context

Revd Amanda Mallen reflects on the impact Church Action on Poverty Sunday made in her community. During the week following Church Action on Poverty Sunday …

We’re listening!

Read some findings from our 2024 survey and in-depth conversations with partners and supporters.

Briefing: New Government data further undermines its cuts to UK’s vital lifelines

The Government’s own statistics show that disabled people are already three times as likely to be living in food insecurity …